- JEPAA Member

- Calligraphy

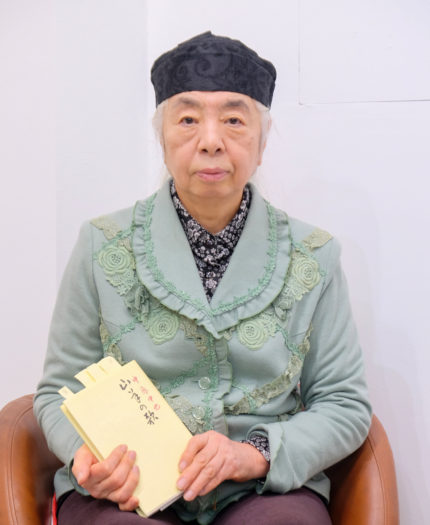

- Miwako Nagaoka

- 書道

- 長岡美和子

© 2024 Miwako Nagaoka.

SCROLL

Portfolio /作品

- 帯/obi

- 奥/inside

- 滑/smooth

Interview article /対談記事

ゲルマー・トモコ(以下、ゲルマー):長岡先生とは何度もお会いさせていただいておりますね。早速ですが今日お持ちいただいたこちらの作品についてお伺いできますでしょうか。

長岡美和子(以下、長岡):こちらの作品は私の41回目の個展で発表したものです。私は文学作品から着想を得て、浮かんだ一字を書すという取り組みを行っており、その41回目の個展でテーマで選んだものが中原中也の詩集でした。

以前金沢へ行ったときに、偶然ある神社に立ち寄ったことがありまして、境内にある大きな木が目に止まったので根元まで行ってみると、そこに立札で「この木の下で中原中也は「サーカス」の着想を得た」と書いてあったんですね。その時からいつか中原中也の詩を使わせてもらいたいなと思っていたんです。それで今から一年前ぐらいですかね。神保町の古本屋へ探しに行きまして、この復刻版の本を見つけたんです。

私は本を読んでいる時、これっていう文字が思い浮かんだら、すっと活字の中から一字がふっと立ち上がってくるんですよ。だからこれって決めて書いたわけではない。100個くらい書いて、その幾つかが作品になります。

ゲルマー:文字が浮かび上がってくるというのは非常に興味深いですね。その一字には長岡先生がどう感じたかが集約されているように感じます。先生は本を読む時決まった進め方があるのでしょうか。

長岡:私の場合はまず全てに目を通し、次に読むときに浮かび上がった一字を書き出していきます。

ただこの一字書を見ていただく時には、私がどう思ったかではなくて、見る方がその本を読んでどう感じたかを大切にしてもらった方がいいですね。私は自由に書いているので、作品を見た方にも固定概念を捨てて自由に受け取ってもらいたいです。ただ、いきなり中也の詩を読んで理解すると言っても難しいですけど。

ゲルマー:確かに固定概念に縛られない、自由な作風がドイツでも好評でした。

しかし昨年からのコロナのパンデミックのせいで、日常生活というものが大きく変わってしまいました。創作活動にも影響があったかと思うのですが、発生当時はどんなことを思われましたか?

長岡:とにかく大変なことになったなと思いましたね。私も戦後生まれで、戦争の大変さは実感としてはありません。社会の危機を目の当たりにしたことがありませんでしたから。コロナは自分の命に関わるし、相手の命を奪うかもしれない。こんな経験は初めてで、どうしたらいいかわからない。ただ目の前のことをしっかりやっていこうと思いました。

しかし、外出の自粛を求められたのは辛かったです。私の中で作品は感動して仕上がるもの。家の中では作品を書ける時間は多いですけど、感動は少ない。私にとって色々な感性に触れることは制作をする上で非常に重要なことなんです。

ゲルマー:なるほど、その時々の感動がないと完成しないものなんですね。色々なものに触れることで感性を磨かれ、それが作品の基礎となっていくんですね。

長岡:はい。ただただ終息を願うばかりです。話は変わりますが、ゲルマーさんから見て日本人とドイツ人が根本的に違うと感じられる部分はどこですか。

ゲルマー:人間としてはみんな同じだとは思います。ただ違いがあるとすれば民族的な部分、「文化」の違いです。ドイツでは日本に比べて自分の意見を述べる機会が多くあります。そこで自分の考え方を持たないのは無知だと思われる。だからこそ個を尊重する土俵がありますね。

長岡:私は自分の意見を言ってしまう方ですけど、確かに日本人は世界から見て自分の意見を言えないと言われていますもんね。日本は逆に意見を言わないことの方が慎ましい、察することが思いやりという美徳があります。しかし芸術や墨象の世界ではそうではいられない。

ゲルマー:そうですね。芸術の世界では自分の世界をどう表現するかという一点に尽きるので、自分の意見や見方がないというのはあり得ないですものね。

長岡:書道の場合は一般的にきれいに書くことが基本と思われています。実際書道をする方に多いのはきれいに書く書道の方です。しかしきれいに書くという目的が達成されればそれで目的は達成されます。そこに感情とかはいらない。

私は書芸術を表現するものとして自分の感情や考え方はとても大切にしています。それを表現できるのが墨象という世界です。

ゲルマー:感情や意志があるからこそ、先生の作品は言葉の違う海外の大勢の方たちにも伝わっていますものね。ちなみに先生はどのような経緯で書を始められたんですか。

長岡:私は大学で書道を勉強したかったのですが、そのような学校はなかったので一般の大学に入り、そこのクラブ活動で書を始めました。そこの顧問だったのが酒井葩雪先生で、「墨象」はその師匠だった上田桑鳩先生によって発案されたものです。「墨象」と呼ばれるようになったのはなぜかと言いますと、書はもともと「心得」だったんです。きれいに書くというのはお茶やお花と同じように心得です。いわゆる教養です。尊敬されるべき人は綺麗な字であるべきというものです。しかしそれは芸術ではありません。対して墨象というのは心得ではなくて、自身の感情が表すことのできる書芸術と上田先生は考えたわけです。

私は書道を始めるまでは「墨象」を知らなかったのですが、書きたいものを書いていくうちに「墨象」の世界へと進んでいきました。その出会いがなかったら、今の私はなかったと思います。上田先生の考えとは違うかもしれないですけど、私は私なりに考えて、表現できればいいと思っています。

ゲルマー:それはもう運命と呼ぶしかないですね。もちろん選択をするときにその選択を可能にする感性があったからなのでしょうけれども。最後に今後作品の制作や活動への抱負があれば教えていただけますか。

長岡:私は計画を立てて制作をしているわけではないですし、またスローガンを掲げてそれに近づいて活動をしているわけでもない。それは一字を選ぶときも同じです。以前「作品にする言葉はどう選ぶのですか」と聞かれたことがありました。しかし私の場合は本が教えてくれますし、作品が教えてくれるので選ぶわけではない。作品の方からこっちの方が良いと言ってくれるのでそれを作品にしているだけなんです。確かに何十枚、何百枚と書いてから一つだけを選ぶ作業はしますけど、それも作品が言ってくれる。もうできているとか、もっと書いた方がいいとか。だから目標や計画を掲げるみたいなことはできないんです。

ただいつも変わらずいい作品を作るために邁進していきたいということです。豊かなものを持っている作品を選ばないことには、私の作品もいいものにはならないので感性を磨き続けたいと思います。まだまだ努力し続けたいですね。

ゲルマー:貴重なお話の数々をありがとうございました。本日のお伺いさせていただいた長岡先生の作品の背景にある思いや考え方をお伺いし、それを今後の海外展の時にはしっかりと伝えていかなくてはと強く思いました。まずは4月、パリで開催される日欧宮殿芸術祭2022にて作品と共に今日のことをお伝えさせていただきますのでよろしくお願い致します。

長岡:よろしくお願い致します。本日はありがとうございました。

(2022年特別対談 長岡美和子×ゲルマー・トモコ)

A seeker of the art of “bokusho” who devotes herself to the path of calligraphy, day in and day out

Tomoko Germar: Ms. Nagaoka, we have met many times, and each time, I am always astonished by your new works. Thank you very much for bringing new work this time as well.

Miwako Nagaoka: This piece was presented at my 41st solo exhibition. I’ve been working on a project in which I am inspired by works of literature, and I depict the characters that come to mind. I read a book, and I write down individual characters that leap out at me from the page. I write about 100 of them, and a few of them will become art pieces.

Germar: It ’s fascinating to see how the characters emerge. It seems to me that each character sums up how you felt about the book. Do you have a specific way of reading books?

Nagaoka: First, I read through the entire book, and then I write down one character that comes to mind when I read it.However, I want the viewer of this single-word calligraphy to take away what he or she feels personally, not what I think of it. I want the viewer to interpret the character as they like, free of fixed stereotypes.

Germar: Your free style, unconstrained by stereotypes, has certainly been well received in Germany. Many people have said that you havechanged the way they view calligraphy.

Nagaoka: Thank you very much. Incidentally, since you have firsthand knowledge of both Japanese and German cultures, what do you feel is the fundamental difference between Japanese and Germans?

Germar: I feel strongly that the differences are cultural. In Germany, you have many opportunities to express your opinions and you have to have your own way of thinking. Because of that, the individual is given a place of respect.

Nagaoka: Personally, I tend to express my own opinions, but in Japan, on the contrary, it is considered more virtuous to be modest and not to express one’s opinions, and to consider the needs of others. But in the world of art and ink painting, this is not the case.

Germar: Yes, that’s right. In the world of art, it’s all about how you express your inner world, so it’s impossible to avoid having your own opinions and views.

Nagaoka: I value my own feelings and thoughts very much, as someone who expresses them through the art of calligraphy. I can express them in the world of“bokusho”(calligraphy ink art).

Germar: It is because of your emotions and your will that your pieces speak to many people overseas, although they may have different languages. By the way, how did you get started in calligraphy?

Nagaoka: I started calligraphy when I joined a calligraphy club at university. My advisor at the club was Hasetsu Sakai, and the art of “bokusho”(calligraphy ink art) was invented by his teacher, Sokyu Ueda.The reason why the avant-garde calligraphy created by these masters came to be called “bokusho”is that calligraphy was originally called“kokoroe,”which implied certain rules to follow. This came from the common notion that a respectable person should have beautiful handwriting. In contrast, Ueda believed that “bokusho”was an art form that could express one’s feelings, rather than a set of“kokoroe” rules. I didn’t know about“bokusho”until after I started calligraphy, but as I simply kept drawing what I wanted to draw, I entered the world of “bokusho.”If I had not had that encounter, I would not be where I am today. My way may not be the same as Ueda’s, but I hope I’m able to think for myself and express myself in my own way.

Germar: I think it’s destiny. Finally, do you have any aspirations for your future work and activities?

Nagaoka: When I create my work, I don’t make plans. It’s the same when I choose a character to paint. When I creatie a piece, I don’t choose the character that leaps out at me from the book. The book or the pieces tells me that it is better this way or that, so I just make it into a work of art. It is true that after writing dozens or hundreds of pages, in the end I choose only one, but the work tells me that, too. They tell it’s already complete, or that I need to do more. So I can’t set goals or make plans. I just want to keep driving forward to create good art, just as I always do. I want to keep improving my sensitivity, because my work will not be as good as it could be if I don’t choose works that have something enriching to offer. I still intend to keep striving.

Germar: Thank you very much for this valuable discussion today. I will be sure to convey what you have said today in future overseas exhibitions.

Nagaoka: I would be very pleased. Thank you very much for your time today.

(Special Talk Session in 2022, Miwako Nagaoka and Tomoko Germer)

書、文学、言語・・・

文化の源を思索する至福のひととき

カトリン=スザンネ・シュミット(以下 シュミット):長岡先生とは今年の 4 月にパリでお会いして以来ですね。しかし今回の池袋展にも、素晴らしい新作をご用意していただき、ありがとうございます。早速ですがこちらの作品からお伺いしてもいいですか。

長岡美和子(以下 長岡):これは「贈」という字を書いています。英語では「gift」ですかね。貝に曽と書いて「贈」となります。今回は永井龍男の「散歩者」から選んだ一字を書きました。

シュミット:この一字書シリーズは、長岡先生が文学作品から着想を得て、浮かんだ一字を書すという独自の取り組みですね。「贈」という字は心を表すいい言葉です。

長岡:そうですね。ただ文章の中から取っているので、使われる意味合いは少し変わってくるかもしれません。私の場合は本を読んでいて、一字がふっと浮いて出てくる。それを書いているだけですけれど、見た方が感じてくれた意味でいいかなと思っています。

シュミット:よく考えましたね。出会って 10 年近く経ちますが、長岡先生の感性や取り組みの切り口は新鮮だと思います。ちなみに題材にする本は、どのようにして選んで、それをどのように作品にしていくんでしょうか。

長岡:大体 10 月末に毎年個展がありますので、それが終わった段階で次の作品に取り組むようにしております。とくに選び方のルールはありませんね。持っている本から選ぶこともあれば、古書店に行ってテーマを探すこともあります。目星をつけて本屋に足を運んでも、その時々の感情で選ぶ本は変わるので、色々手に取って読むようにしていますね。

シュミット:作品を仕上げる時は、何枚も書くのですか?

長岡:何枚も書くこともあれば数枚で満足できることもあります。自分の心に敵うものでなければ作品にはいたしません。だから本を読み込む時間の方が長いです。どの本にするか読み込みながら、やっと一字が決まります。

シュミット:この取り組みはもう何年くらいされていますか?

長岡:17 年が経ちました。元々は普通に書いていたのですが、鍛錬を続けているうちに、気づいたら文学から字を取れるようになっていました。私からも質問してよろしいですか? シュミットさんはドイツでどのような教育を受けてこられましたか。

シュミット:私は旧東ドイツの小さい町に生まれて、高等学校の校長先生の父と薬局に勤務していた母は薬局でずっと働いていました。高校までは同じ街で過ごして、大学からベルリンに行き、日本学科で 5 年間日本の言葉と文化を学びました。芸術を勉強したのも、同じ時期ですね。

長岡:日本に興味を持たれたのはなぜですか。

シュミット:日本に関心のある友人がいたのです。その友人はわびさびについて少し興味があり、私も感銘を受けたことが大きかったですね。それと言語ですね。英語もフランス語も面白かったですが、中でも日本語は面白いと思いました。

長岡:そこの国の文化を知りたいと思ったわけですね。言葉を知るというのは文化を知ることですもんね。でも大学生の頃からわびさびに関心があったというのは驚きです。日本人でもわからない人は多いですから。

シュミット:そうですね。ヨーロッパでは日本の理想的な美意識がわびさびだということを知っている方は多いですね。今はアニメとか漫画の印象の方が強いと思いますが。

長岡:日本には「教養」や「心得」という言葉があります。日本人ならこうありたい、こうあるべきというものですね。それがわびさびへと繋がっていきましたけど、絵を美しく描く、字を綺麗に書くというのは心得だったんですね。

シュミット:大学の時代に書や花を学びましたが、すごく難しくて今はやっていません。ただ日本の精神を感じる作品にはいつも惹かれます。少し違うかもしれませんが、知り合いのデザイナーが雨をザーザー、ぽつぽつといろんな種類で表現していたのを見たときにすごく感動しました。

長岡:ドイツにはそのような表現はないですか。

シュミット:ないですね。強い雨が降っているとか、弱い雨とかそういった表現です。日本語は面白いです。

長岡:ドイツと日本の人たちは気質が似ていると言われていますがシュミットさんはどう感じますか。

シュミット:確かに日本人はアジアのドイツ人という風に親しみを持って言われていた時はありましたけど、80 年代以降の若い世代はそうとも言い切れないですね。非常に多様です。国で括れないです。話を作品に戻しますが、これから制作で取り組んでみたいことはありますか。

長岡:ないですね。制作は感情でできるのでその瞬間瞬間で変わると思います。制作をする上で目標を持つということはすごく難しいですね。

シュミット:なるほど、その時どきのベストの長岡先生の作品を期待しております。今日はありがとうございました。

(2022年特別対談 長岡美和子×カトリン=スザンネ・シュミット)

Calligraphy, literature, language… A blissful moment contemplating the origins of culture

Katrin-Susanne Schmidt: I last saw you, Ms. Nagaoka, in Paris in April of this year. Thank you for preparing wonderful new artwork again for the Ikebukuro exhibition. May I begin by asking you about this work?

Nagaoka Miwako: Here I have written the character“Zou.”In English I think it translates as“gift.”It is written with parts that mean “currency”and“to layer.”For this occasion I wrote a single character chosen from“Walker” by Nagai Tatsuo.

Schmidt: For this single character series, I believe you work in a unique way by receiving inspiration from a work of literature, and writing a character that comes to mind. The character “Zou (gift)”is a fine word expressing the heart.

Nagaoka: Yes. However, since I take it from out of the text, the nuance used may change a little. I find I am reading a book, and a single character suddenly jumps out at me. I merely write the character—I am happy with the meaning with which the viewer senses it.

Schmidt: That is well thought out. It’s nearly 10 years since we first met each other, but I think your sentiment and approach to your work is fresh and new. I wonder how you choose the books you use as material, and how you create an artwork from them?

Nagaoka: I usually hold an annual solo exhibition at the end of October, and once that is finished, I set to work on the next artworks. There are no rules particularly for how I choose. Sometimes I choose from the books I have, while sometimes I go to an antiquarian bookstore and look for a theme. Even if I fix my choice and visit a bookstore, the book I choose changes with my feelings when I get there, so I try to get hold of various ones to read.

Schmidt: Do you write it on many sheets before the artwork is complete?

Nagaoka: Sometimes it takes many sheets, while sometimes I am satisfied after a few sheets. If it is not something that satisfies my heart, I will never make it an artwork. So the time I spend deeply reading the book is longer. While I am deeply reading to decide which book to choose, eventually a single character will decide itself.

Schmidt: How many years have you been carrying this out?

Nagaoka: It’s been 17 years. I started by writing normal calligraphy, but as my training continued I noticed that I was taking characters from works of literature. May I also ask a question? Ms. Schmidt, what kind of education did you receive in Germany?

Schmidt: I was born in a small town in the former East Germany. My father was headmaster of a senior high school, and my mother who worked in a pharmacy was always working there. I spent my high school days in the same town, and for university I went to Berlin, where I studied Japanese language and culture for five years in the Japanese Department. It was during that time that I also studied art.

Nagaoka: Why did you have an interest in Japan?

Schmidt: I had a friend who was interested in Japan. That friend had some interest in wabi-sabi, and I was also impressed by it and that had a great impact, I think. And also the language. English and French were interesting, but I found Japanese even more interesting.

Nagaoka: So you thought you’d like to learn about the culture of the country, I guess. Learning a language is the same as learning about a culture, isn’t it? But I’m surprised to hear you were interested in wabi-sabi while you were a student. There are many Japanese people who don’t understand it.

Schmidt: Yes. There are many people in Europe who know that the Japanese ideal aesthetic sense is called wabi-sabi. Although I think there is a stronger impression nowadays from things like anime and manga.

Nagaoka: In Japan there are the words“general knowledge”and“things to keep in mind.”They mean that as a Japanese person I want to be like this, I should be like this. They continue to be connected to wabi-sabi, but painting pictures beautifully, and writing characters neatly is to do with“things to keep in mind.”

Schmidt: During my university days I studied calligraphy and flower arrangement, but I found them very difficult and I no longer do them. However I always admire artwork that gives a sense of the Japanese spirit.It might be a bit different, but a designer who I know portrayed rain using various different expressions like“za-za,”“potsu-potsu,”and when I saw it I was very impressed.

Nagaoka: Aren’t there any expressions like that in Germany?

Schmidt: No, there aren’t. We have expressions such as heavy rain, light rain. Japanese is interesting.

Nagaoka: It is said that the people of Germany and Japan have similar demeanors, but Ms. Schmidt, what do you think?

Schmidt: There was certainly a time when Japanese people were affectionately called the Germans of Asia, but I’m not so sure about the young generation since the 1980s. They are extremely diverse. They are not constricted to a country.Returning to your artwork, is there anything you would like to try from now?

Nagaoka: No, there aren’t. I produce artwork from my emotions, so I think things change from moment to moment. It’s very difficult to have a goal in producing artwork.

Schmidt: I see, so I look forward to your best artwork at each of the moments.Thank you very much for your time today.

(Special Talk Session in 2022, Miwako Nagaoka and Katrin-Susanne Schmidt )

「長岡先生のかすれは本当に美しいですね」

ハイケ・イェローミン(以下ハイケ):長岡先生とは、2019年春の日欧宮殿芸術祭(ウィーン)以来となりますね。お久しぶりです。あの時は素晴らしい揮毫を披露していただき、ありがとうございました。今日は先生の書の創作についてお伺いしたいと思います。まず、今回お持ちいただいた「匂」についてお聞かせください。

長岡美和子(以下長岡):こちらの「匂」という字は、「漂」にも意味の通じるところがありますね。花の香りのような嗅覚を刺激するものではなく、気配とか、存在とかを示すような意味合いも兼ねていると。この作品、題材を三浦朱門の「冥府山水図」からとった作品で、物語は、山水画の絵師たちが、絶景を求めて山の奥深くまで分け入っていく苦悩が語られていまして、多くの絵師が険しさに挫折する中で、遂に絶景に到達した絵師の一人がそれを描くのだけれども、実物の素晴らしさにはまったく及ばないことを思い知らされるんですね。そして最後にはその絵師も息絶えて土に還り、匂いくらいしか残らないと。

長岡美和子氏

ハイケ:それで、「匂」が出てきたのですね。それは小説の中に、実際に使われている字なのですか?

長岡:えぇ、ページの中から、最も物語を象徴する字が、読んでいるうちにスッと浮かび上がってくるんです。これは、私が長年手がけている表現のスタイルで、これ以外にも様々な本をテーマにして、書を表してきました。

ハイケ:とてもインテリジェンスがあり、魅力的な表現ですね。私は長岡先生の書を見て、とくにかすれが美しいと感じました。このかすれの表現というのは、どうやって書いて、どのように違いを作り出すのでしょうか?

長岡:書き方、筆遣いはもちろんですが、墨の質による違いが大きいと思います。硯で墨を擦る時に力を加えれば濃くなりますし、粘り気も強くなる。水の配分で薄くなったり、紙への浸透の仕方も変わってきますね。そもそも墨自体も、純粋な黒とは違いますから、物によって擦った時、水を入れた時の色の具合が変わってきます。鼠色ということもありますが、それはあくまで墨の色のほんの一面に過ぎません。それを、筆一本で書き切っていくわけです。

ハイケ:それを実際にできるようになるには、多くの経験が必要ですよね。

長岡:仰るとおりです。例えば私が作品を書くのに使う筆は、非常に穂の部分が長く、全体に墨をしっかりと行き渡らせてから書き始めます。含まれた墨だけで最後まで書き切るため、穂全体を使わないように気を配りながら進めていくんです。ただ、べたべたに墨を漬け過ぎてもいけません。ちょうど使い切れる量を、適度に筆先に落としながら書けるようになるには、とにかく数多く書いて覚えるのが大切です。

ハイケ:ウィーンで見た揮毫で思ったのが、体の動きが武術の居合道のようだということです。先生は居合道をやっているとお聞きしましたが、書に活かされることなどはありますか?

長岡:書道は全身を使って書いていきますから、その点では共通します。ただし居合道でなくとも、合気道や剣道など、武術は細かな技術こそ違いますが、呼吸法など根っこの部分では同じであり、それは書道にも必要なことですね。

ハイケ:実は先生お会いするにあたり、墨象についても学びました。墨象は中国の書にはない日本独自の書芸術であり、アメリカの抽象表現やアクションペインティングにも影響を与えるなど、すでに世界基準のアートとなっています。そして、その分野で優れた成果を残している長岡先生とお会いして、改めてそのすごさを実感しました。今日も色々と教わりましたが、やはりかすれの美しさですね。本当に感激しました。ぜひこれからも素晴らしい書の世界を表現してください。

長岡:ありがとうございます。個人的にもかすれのある書は好きなのです。なぜなら、難しいから。難しい方が面白いじゃないですか。

ハイケ:素晴らしい。そのお気持ち、まさに本物の芸術家だと思います。

(2019年特別対談 長岡美和子×ハイケ・イェローミン)

“The blur effect of Nagaoka’s work is truly beautiful”

Heike Jeromin (hereinafter referred to as “Heike”): Ms. Nagaoka, this is the first time I’ve seen you since the Spring 2019 Japan-Europe Palace Art Festival (Vienna). So it’s been a while. Thank you for showing me your work during that time. As for today, I’d like to ask you about the creation of your calligraphy work. So please start off by telling me about the “Scent” piece that you brought with you today.

Miwako Nagaoka (hereinafter referred to as “Nagaoka”): In a sense, the word “scent” here can be interpreted to mean “drift.” The word does not refer to the way one’s sense of smell is stimulated by something such as the fragrance of a flower. It does, however, contain the nuance of being an indicator of a “sign” or “presence.” This piece takes on the theme of a short story by Shumon Miura titled “The Landscape of Mountain.” The piece tells a story of the grievances faced by landscape painters who travelled deep into the mountains in search of a picturesque view. While many painters suffered setbacks due to the harsh nature of the journey, there was one painter who was able to find this picturesque view and painted it at last. However, he then realized that his painting was never going to live up to the true splendor of the actual scenery. So in the end, the painter took his last breathe and was buried back into the soil, leaving nothing but a scent.

Heike: So that’s how the “Scent” piece came into being. But was the “scent” character actually used in the novel?

Nagaoka: Yes. It was the most symbolic character within the pages of the story. It popped out to me immediately as I was reading. This is also a style of expression that I’ve worked on for many years. Besides this, I’ve also done other calligraphy pieces where I’ve used a variety of books as the theme.

Heike: It’s a very smart and captivating form of expression. When I looked at your works, I felt that the blur effect was especially beautiful. So how do you create these blurs and how do you make them different from one another?

Nagaoka: Using different writing techniques and changing my brushwork definitely allows me to alter the appearance of the blur. But I think it also differs greatly depending on the quality of the ink. If I apply force when rubbing the ink against the inkstone, the ink will become dark and sticky as a result. But when I mix the ink with water, it becomes diluted, which also changes the way the ink seeps into paper. The ink itself is not purely black by nature, so the color I get when rubbing it against something will differ from the color I get when it’s mixed with water. There’re also times when the ink is grey. But that’s nothing more than just one of the aspects of the ink’s color. It’s something that can be produced on paper with just a single brush.

Heike: To be able to do this actually requires a lot of experience, doesn’t it?

Nagaoka: You’re absolutely right. For instance, the brush I use to write my calligraphy pieces has to have a very long tip. Plus I’m only able to begin writing after I’ve thoroughly spreaded the ink throughout the brush tip. I also have to complete the calligraphy piece in one go with only the ink that’s on the brush. Because of this, I have to be mindful not to use all the ink on the brush tip as I’m writing. But at the same time, I also have to make sure not to use too much ink and not to make it sticky. It’s important to practice many times over when learning how to use just the right amount of ink to finish a piece and to learn how to write while using the moderate amount of ink on the brush tip.

Heike: When I saw your work in Vienna, the thought that came to mind was that the movement of the body is like the martial art of iaido. I heard that you’re doing iaido. But do you ever apply anything from iaido into your calligraphy work?

Nagaoka: Calligraphy is similar to iaodo in that it requires the whole body to be used. But other than iaido, martial arts such as aikido and kendo all differ from each other in terms of the detailed techniques used. Despite this, they’re also the same as each other at a base level, since they share certain qualities that are the same such as breathing techniques. This sort of thing is also necessary in calligraphy.

Heike: Actually, when I met you, I also learned about the practice of bokusho (ink images). Bokusho is a form of calligraphy that is unique to Japan and unseen in Chinese calligraphy. It has already become a world-standard form of art that influences abstract expressions and action paintings in America. Also, after meeting a person like you who has accomplished great achievements in the field, I once again felt how wonderful the art form is. I learned a lot from you today, but I was truly moved by the beauty of the blur effect. So please continue to portray the wonderful world of calligraphy from now on.

Nagaoka: Thank you very much. I personally like calligraphy pieces with the blur effect too. Because it’s difficult to achieve. Isn’t it more interesting when something is difficult?

Heike: That’s great. Hearing you say that makes me think that you’re indeed a true artist.

(Special Talk Session in 2022, Miwako Nagaoka and Heike Jeromin )

Solo Exhibition /個展

特設個展ブースin アジアジャパンアートビエンナーレ2020

会期:2020年6月4日~6日

会場:アートハウス(シンガポール)

主催:一般社団法人 日欧宮殿芸術協会

運営:クリエイト・アイエムエス株式会社

Special Exhibition Booth in Asia Japan Art Biennale 2020

Dates: June 4-6, 2020

Venue: Art House, Singapore

Organizer: Japan-Europe Palace Art Association

Operated by: Create IMS Co.

Profile /経歴

長岡美和子 Miwako Nagaoka

1945年 富山県出身

近畿大学理工学部卒

師:上田桑鳩

作品出展国遍歴(JEPAA関連事業):ドイツ、フランス、イタリア、カナダ他

Born: 1945 Toyama, Japan

Education: Faculty of Science and Engineering, KINKI University, Osaka

Master: Sokyu Ueda

Exhibition of Works(JEPAA): Germany, France, Italy, Canada…