- JEPAA Member

- Artist

- Hiroko Gujo

- 芸術家

- 公庄弘子

© 2024 Hiroko Gujo.

SCROLL

Portfolio /作品一覧

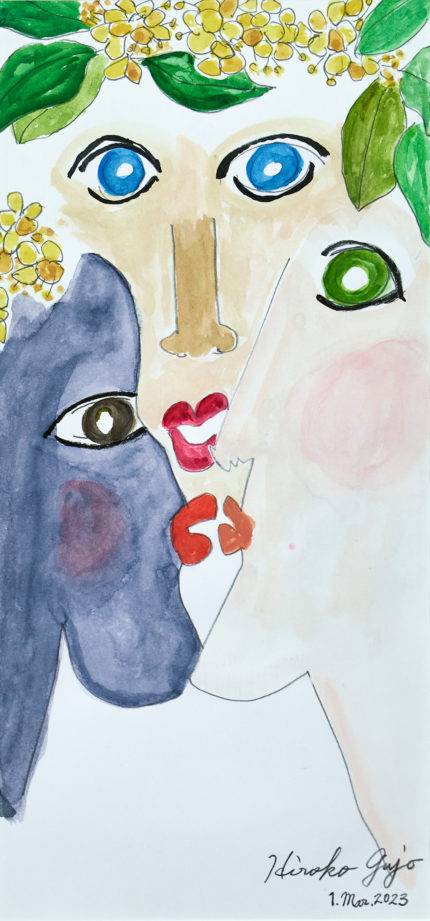

- chat chat chat(談笑)

- Happy joyful(嬉しい!)

- Talk Talk Talk

Interview article /対談記事

2023年特別対談 公庄弘子×ジョゼフ・バルバラ

自由な心が色鮮やかに踊る

内面表現の世界

ジョゼフ・バルバラ(以下 ジョゼフ):公庄先生の作品は、マルタの展覧会でも拝見していました。私は 画家なので公庄先生の絵の方のイメージが強く残っているのですが、今回は立体作品を出してくださったのですね。よろしければご解説をお願いします。

公庄弘子(以下 公庄):私は花が好きなので、見方次第でオブジェでも花活けでも、どちらにも取れるものを制作しました。その時にパッと思いついたままに自由に作っていくのが私のやり方なんです。

ジョゼフ:それは素晴らしい。色もとても美しいです。ちなみにこの作品はろくろを使ったのでしょうか? それとも手捻りですか?

公庄:手捻りですね。自分で粘土を自由に捏ねなが ら、まさにその時のイメージのままに作りました。

ジョゼフ:やはりそうですか。そのイメージを膨らませながら作り上げた工程が、作品から伝わってきて良 いと思います。ところで私は公庄先生の絵にも興味が あるのですが、制作の時はどのようなモチーフを考え ることが多いですか?

公庄:テーマなどを設けて描くことはあまり無いよう に思います。私の場合は、その時の心の中にあるもの を自分の外側に出すという感じです。例えば、葛藤か らの解放であったりとか、仕事を離れて気持ちを新た にした時などですね。ですから、表現したい気持ちが 心から湧き上がってくることが大事です。

ジョゼフ:作品を見ていると、その時々の気持ちが色 彩として表現されているように思えるのですが、いか がでしょうか?

公庄:そうかもしれません。ただ私は計画的に描いて いるわけではないので、『こういう気持ちだからこの 色を使おう』という風に一つ一つ理由や意図を説明す るのは難しいですね。瞬間的な閃きなので、『気がつい たらこうなっていた』ということが多いです。

ジョゼフ:私は公庄先生が明るい色で描いた作品が好 きですね。きっと気持ちも明るく幸せな時だったと思 いますから。

公庄:ありがとうございます。

ジョゼフ:いまお話を聞いただけでも公庄先生の創作 はかなり個性的だと思うのですが、先生はいつ頃から 芸術活動をやっているんでしょうか?

公庄:私にとっての芸術の原点は、遊びの泥団子なん ですよ。子どもたちはみんなやるでしょう?でも私 は自由にやらせてもらえなくて、その時の気持ちが大 人になるまでずっと胸に残っていたんです。 学校を卒業後、小学校の教師に採用されました。最初 に赴任したのは僻地の学校でしたが、素晴らしい先輩 の先生方と子ども達に出会いました。教育環境も非常 に充実していました。そして、幸運なことに研究指定 校の全国発表直後の学校で、地域と学校が一丸となっ て取り組んでおられたのが非常に印象的でした。25歳 の時に京都市内に移動しました。そこで学校の教職員 の陶芸サークルの立ち上げに参加したんですね。身近 に清水焼などの陶磁器の窯があったことも影響したの かもしれません。1984年ごろからはインスタレーショ ンにも興味が移っていきました。紙や木、石、布など を使って制作するのは楽しかったですね。 でも仕事が忙しくなってだんだんアートと離れていき ました。改めて何かやりたい気持ちになったのは、教師を辞めてからですね。時間ができて、油絵の教室に 通い始めました。

ジョゼフ:なるほど、私が知っている陶芸や水彩画は ほんの一部だったのですね。

公庄:でも母親の介護でまた忙しくなって絵から離れ ました。それが終わってようやく始めたのが水彩画で す。

ジョゼフ:これまで色々な芸術を経験されてこられた わけですが、今後何かやりたいことはありますか?

公庄:はっきりとした予定はありませんが、家にある 古い腕時計があるので、それをリメイクして何か作っ てみたいですね。長年愛用してきたものを甦らせる行 為自体が好きなんですよ。

ジョゼフ:それはとても素晴らしい考えですね。

公庄:別に道具に限ったことではなくて、例えば花屋 さんで処分寸前な鉢植えの草花とかを見かけたら、な んとかしたいと思っちゃうんですね。だから引き取っ て家で世話してまた元気になったりするのが、とても楽しいんですよ。

ジョゼフ:私も海岸に捨てられたペットボトルなどの 廃棄物を再利用してインスタレーションを制作したこ とがあります。ですから公庄先生の何かを甦らせよう とする気持ちには非常に深く共感できますし、創作のための精神として変換できることは素敵だと思いま す。ぜひこれからも自由な気持ちで絵や陶芸を頑張っ てください。今日はありがとうございました。

公庄:こちらこそ、ありがとうございました。

Special Talk Session Hiroko Gujo×Katrin-Susanne Schmidt,2023

Expressing the Inner Landscapes with a Free and Joyous Spirit

Joseph Barbara: I saw your works at the Malta exhibition. I’m a painter, too, so your pieces had a strong impression on me. For this time, though, it looks like you’ve made a 3D piece. Could you talk about it a little?

Hiroko Gujo: As someone fond of flowers, I want to make a piece that could be seen as either an objets d’art or flower vase. My style is to just start making whatever pops into my mind.

Joseph: I think that’s wonderful. The colors are so beautiful, too. Did you use a potter’s wheel for this? Or did you form it by hand?

Gujo: By hand. I worked it up with clay until it was exactly what I had in mind.

Joseph: I thought so. The piece shows your process of gradually giving form to an image in your mind, and I think that’s great. I find your paintings interesting, too. What kinds of motifs do you usually think about when you paint?

Gujo: I hardly ever paint with some theme or concept in mind. For me, it’s more like taking what’s in my heart in the moment and expressing it externally. Those moments might be when the stress of some conflict has passed, or when I’m taking a breather away from work. That’s why it’s important that the feeling I’m trying to express wells up from my heart.

Joseph: Your pieces seem to express in color what you are feeling at different times. Would that be accurate to say?

Gujo: That might be. But I don’t plan a piece beforehand. I wouldn’t be able to explain every little reason or intention I had, like “I used this color because I was feeling this way.” A feeling will usually just hit me, and I’ll finish painting before even noticing how I was feeling.

Joseph: I really like how you use bright colors. It makes me think you were in good spirits at the time.

Gujo: Thank you.

Joseph: Just what you’ve told me so far makes me think that your process is very unique. When did you first start making art?

Gujo: Art for me began with dorodango (forming earth and water into a polished sphere) that I made for fun. Every kid makes those, right? But I wasn’t allowed to make them how I wanted, and the feelings I had about that stayed with me all the way until I became an adult. After graduating from school, I was hired as an elementary school teacher. The first school I was sent to was in the middle of nowhere, and I met some really great teachers and kids there. The school had a first-rate educational environment. I was also lucky in that the school had just been designated as a school for research and development, so the community and school worked together on things. I’ll never forget the experience. When I was 25, I moved to Kyoto and got a job at a different school. I helped start a ceramics club there for the teachers. I guess my process now was influenced by the fact that they had a ceramic kiln, which I often used to make things like Kiyomizu ware. It was around 1984 that my interest turned to art installations. I enjoyed making things out of materials like paper, wood, stone, and fabric. But my work got busy and I slowly drifted away from art. It wasn’t until I quit teaching that I regained an interest in doing something with art. I had the time, so I started taking oil painting classes.

Joseph: So your ceramic pieces and watercolor paintings that I know are just a small slice of everything you’ve done.

Gujo: But I got away from painting once again when I got busy taking care of my mother. When that ended, I finally began doing watercolors.

Joseph: You have experienced such a rich variety of art forms. Is there anything in particular you want to do going forward?

Gujo: I don’t have any special plan, but I have this old watch at my house that I’m thinking of remaking into something else. I like giving new life to things that people have gotten good use out of over the years. Joseph: That’s a wonderful idea.

Gujo: And it doesn’t have to be a tool; I’ll see a potted flower or plant about to be thrown away at a florist and just get the urge to do something with it. I’ll take it home, care for it, and see it get well again. That’s a lot of fun for me.

Joseph: I’ve taken trash like a plastic bottle I found on the beach and reused it as part of an art installation. Your inclination to reuse things strikes a deep chord with me. I think it’s wonderful that you can inhabit that spirit for making new things. I wish you the best of luck in the future painting and making ceramics as the mood strikes you. Thank you for talking with me today.

Gujo: The pleasure was mine.

2022年特別対談 公庄弘子×カトリン=スザンネ・シュミット

自由な創造力の源は、母との思い出と童心

カトリン=スザンネ・シュミット(以下 シュミット):公庄弘子様は、お母様の恵風先生と二代で芸術活動をなさっていらっしゃいますね。でも母娘で違うジャンルをやっているというのがとても面白いと思っていました。お母様の恵風先生は、水墨画家でいらっしゃいますね。作品は展覧会でよく拝見していました。とても日本の伝統を大切にした絵画だなといつも感心していました。一方の弘子様は、とても自由な創作をなさっていらっしゃいますね。枠に縛られずに表現できるというのは、芸術における大切な才能だと思います。今回の池袋展にもお二人それぞれに作品を出展されていますが、まず弘子さまの作品から解説をお願い致します。

公庄弘子(以下 公庄):この出展作は1986 年頃に制作したものです。40 年くらい前の作品で、その時にどのようなタイトルをつけたかも覚えていないので、あえてそのまま無題としました。作品を見た方には自由に解釈していただければと思っています。

シュミット:弘子様の作品は自由で独創的なので「自由に解釈してほしい」という言葉には弘子様のお人柄が表れているように感じます。ちなみにこれは花瓶ですか?それともオブジェですか?

公庄:私は花瓶のつもりで制作しましたが、見る人がオブジェと捉えたのならそれでいいと考えております。

シュミット:それもまた自由ということですね。こちらの作品にはどんな材料を使われているのでしょうか。

公庄:信しがらき楽(正式名は滋賀県甲賀市信楽町。日本を代表する陶器である信楽焼の産地として知られ、良質な陶芸用の粘土が取れる)の粘土を主に使っていて、そこに砂を少し混ぜています。成形は紐づくりで部分的に削り落としています。乾燥後、電気釜で素焼きします。次に、3 種類の釉薬をかけ、さらにもう一度焼いて(本焼)完成です。

シュミット:非常に手間暇がかかっているのですね。陶芸はドイツでもマイセン(ドイツのマイセン地方で生産される磁器の呼称。1709 年ごろ、錬金術師ベドガーが白磁の生産に成功したのがその起源とされる。名実ともに西洋白磁の頂点に君臨する名窯と言われる)などが盛んなので私も少しは知識があるのですが、実際にお話を聞くとすごく難しい世界なのだと改めて思います。

公庄:釉薬の塗り方で作品の印象が変わるので偶然も楽しみながら制作をしておりました。

シュミット:とても奥が深いですね。次は掛け軸について解説をお願いします。こちらはお母さま、恵風先生の作品ですね。この風景はどちらで見られる景色なんでしょうか? それとも現実にはない想像の景色ですか?

公庄:ここの描かれているのはきっと京都嵐山(京都市西部にある標高382 メートル の山。またその周辺の地名。観光地として有名)の保津川(京都府西部を南東流する川。周辺の峡谷は、川下りや観光トロッコ列車で知られる景勝地であり、京都府立保津峡自然公園に指定されている)だと思います。母の家から私の住む場所に行く道中にこのような風景が見えるところがあります。(JR 西日本の嵯峨野線)おそらく保津川です。ただ母は実際に見て書くというよりは、自身の故郷を思い出して描く人でした。思い出のイメージを膨らませて作品にすることが多かったようです。ある意味で心象表現とも言えます。

シュミット:なるほど、木を一つ取ってみても同じ木はなく、空気感みたいな軽やかさを感じますね。このような空気感をモノクロームで表現できる水墨画家は、改めてすごい芸術家だと思います。ところで恵風先生はいつから水墨をされていたのでしょうか。

公庄:80 歳位からだと思います。30 代から華道の道でスケッチ画を、70 代からは精密な表現の植物画を、その後、もっと大胆な表現を求めて水墨画に移行したようです。

シュミット:では生涯ずっと絵を描かれていたということですね。素晴らしいです。ちなみに恵風先生も弘子様もジャンルは違えど同じ芸術家ですが、弘子様への影響は大きかったのではないですか?

公庄:そうですね。何より芸術が近くにある環境で育ちました。母が大きなケント紙にこけしの絵を描いたことがありましたが、それを絨毯の代わりに和室に敷いて生活をしていたなんてこともあります。

シュミット:芸術が生活の一部になっていたんですね。弘子様はなぜ水墨ではなく陶芸をされたのですか。

公庄:私は小さい頃にどろ遊びができなかったんですよ。子どもの頃は忙しくて遊んでいる暇も無く、子どもらしい遊びが出来ませんでした。だから陶芸をしていると童心にかえれる気がするんです。気がついたら陶芸をしておりましたね。現在はできていませんが陶芸を始めてからかれこれ40 年くらい経ちます。

シュミット:そうだったんですね。なぜ現在は作品制作をされないのですか。

公庄:しないというより今は仕事に追われてできていないという感じです。つい最近まで母の介護で手一杯だったのも理由の一つです。母は103 歳で3 年前に亡くなりました。

シュミット:実は私にも、介護が必要な母がいるんです。ですから弘子様がお一人で介護なさっていることがどれほどすごいことなのかはよく分かります。

公庄:ありがとうございます。私は元々小学校で教師をしていたのですが、早期退職してそれから母の世話をしたという感じです。

シュミット:全ては弘子様のおかげと言えるでしょう。最後になりますが、弘子様がこれからの目標や叶えたいことなどはありますか。

公庄:そうですね。これからは簡単なものでもいいから作品制作をしていけたらいいと思います。そして何をするにも健康が一番ですので、今やっている歌で健康を保ち続けたいですね。

シュミット:実は私も合唱団でコーラスをやっていたので、機会があればいつか一緒に歌いましょう。ぜひお体を大事に、これからも素晴らしい創作を続けてください。本日はありがとうございました。

公庄:はい、私も実現する日が来ることを楽しみにしております。こちらこそありがとうございました。

Special Talk Session Hiroko Gujo×Katrin-Susanne Schmidt,2022

Unrestrained Creativity Flowing from a Fondness for Childhood and Memories of Mother

Katrin-Susanne Schmidt: Hiroko Gujo, you and your mother make up a two-generation artist duo. But I found it very interesting that you both work in different genres. You have each submitted different pieces to the Ikebukuro exhibition, and I would like you to talk about your pieces first.

Hiroko Gujo: I made this piece in 1986 or so. That’s about 40 years ago, and I’ve left it untitled because I don’t remember the title I gave it at the time. I encourage people to interpret the piece however they wish.

Schmidt: Your pieces are creative and unrestrained, and telling people to interpret it as they wish fits with how I see you as a person. By the way, is this a vase? Or is it an objets d’art?

Gujo: I intended it to be a vase, but it’s fine if some people see it as an objets d’art.

Schmidt: One more way in which your art is free. So what materials did you use to make it?

Gujo: I mostly used clay from Shigaraki (located in Shiga Prefecture and known for its production of Shigaraki ware, a famous type of Japanese pottery, as well as for clay used to make high-quality pottery), with a little sand mixed in. The artwork is moulded by step-bystep scraping with string. After drying, I coated it with three kinds of glaze and fired it in an electric kiln. I fired it one more time after to get the final product.

Schmidt: Sounds like it took quite a long time to make.

Gujo: Not really. It only took about a day as the glaze dries fast. Pieces give a different impression depending on how the glaze is applied, so the randomness of the process was also fun.

Schmidt: There’s a lot to making such a piece, it seems. Could you talk about your hanging scroll, next? This is your mother’s (Keifu Sensei’s) piece, correct? What is the view of? Or is this an invented scene from her imagination?

Gujo: I believe this depicts the Hozu River (a river that flows southeastward through Western Kyoto Prefecture) in Arashiyama (a mountain with an elevation of 382 m in the western part of Kyoto City, as well as the name of the area surrounding, which is a popular tourist destination), Kyoto. I’m pretty sure, since there was a view like this on the way to my house from my mother’s. Actually though, my mother would paint scenes of her hometown from memory rather than looking at them as she painted. She often expanded on the scenes in her memory to come up with her pieces. Like expressing a mental picture, if you would.

Schmidt: Interesting. Even focusing on individual trees, no two are alike. There is an airy atmosphere to it. When did Keifu Sensei start working with ink?

Gujo: I remember that she started when she was about 80. She seems to have started sketching in her 30s in the process of learning flower arrangement, learnt how to draw precise botanical paintings in her 70s, and then started learning sumi-ink painting for more dynamic and daring expression.

Schmidt: So she painted all through her life,then. Just fantastic. By the way, both you and your mother are artists, and even though your styles differ, would you say she had a big influence on you?

Gujo: Yes. Growing up in an artistic environment was a big thing. One time she painted an image of a kokeshi doll on a big piece of Kent paper,and used that in place of a rug in one of the Japanese-style rooms in our house.

Schmidt: It sounds like art was a part of your everyday life. Why did you go into pottery instead of ink painting?

Gujo: I didn’t have a chance to play in the mud when I was little. Things kept me busy so I had no time to play as children usually do. Making pottery lets me relive my childhood. Pottery was just something I found myself doing. It has been something like 40 years since I started working with ceramics, even though I don’t do it now.

Schmidt: Why aren’t you making pieces anymore?

Gujo: I’d like to, but my work keeps me too busy. I’ve also had my hands full taking care of my mother until recently. She died three years ago at 103.

Schmidt: I also have a mother in need of care, so I completely understand how amazing it is that you cared for your mother by yourself.

Gujo: Thank you very much. I had been a teacher at an elementary school, but I retired early to take care of my mother.

Schmidt: So she has you to thank for everything.Lastly, are there any goals that you are still working toward?

Gujo: Yes. I’d like to start making art, however simple they are. Health is the most important thing, so I’m going to be focused on staying healthy through my singing.

Schmidt: I also used to sing a chorus, so we should sing together if we ever get a chance. Please take care of yourself and continue to make wonderful art. Thank you very much for your time today.

Gujo: Thank you very much, too.

個展ブース / Solo exhibition

特設個展ブース in 日欧宮殿芸術祭2024

会期:2024年4月20日~22日

会場:シャルロッテンブルク宮殿オランジュリー(ドイツ)

主催:一般社団法人 日欧宮殿芸術協会

運営:クリエイト・アイエムエス株式会社

Special Exhibition Booth in Japan Art Festival 2024

Dates: April 20-22, 2024

Venue: Charlottenburg Palace Orangery,Germany

Organizer: Japan-Europe Palace Art Association

Operated by: Create IMS Co.

Profile /経歴

公庄弘子 Hiroko Gujo

1943年 京都府出身

作品出展国遍歴(JEPAA関連事業):ドイツ、マルタ共和国など

Born:1943,Kyoto

Exhibition of Works(JEPAA): Germany,Malta…

-430x548.jpg)

-430x517.jpg)