- JEPAA Member

- Poems / Tanka

- Yoriko Minegishi

- 詩/短歌

- 峰岸順子

© 2024 Yoriko Minegishi.

SCROLL

Portfolio /作品一覧

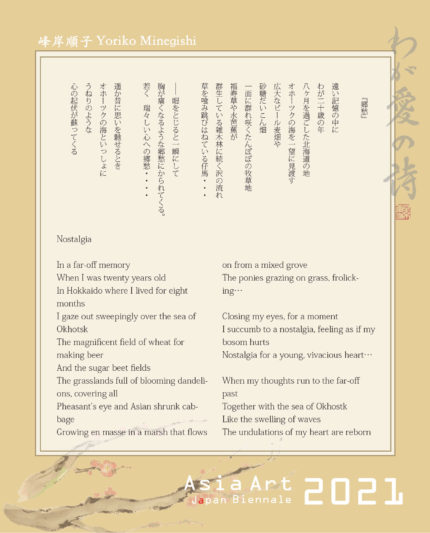

- 郷愁/Nostalgia

- 母は空にいる/My mother is in the sky

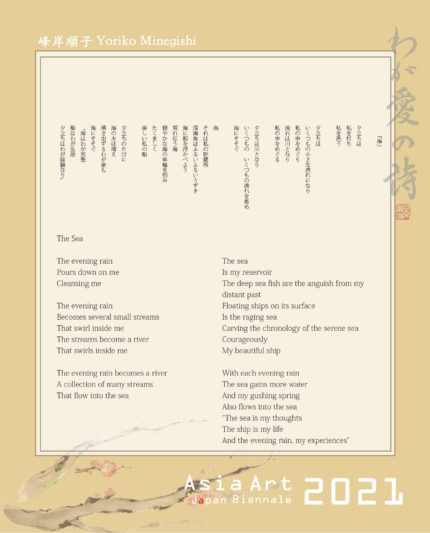

- 海/The Sea

view more

Interview article /対談記事

詩と絵画の代表、ジャンルの枠を超えて創造の源を探る

クラウス・メンツ・ザンダー(以下、ザンダー):本日は、詩人である峰岸先生と、画家である私で、表現方法の違いや、峰岸先生の詩に対する思いについて話して行ければと思います。まず、今回の出品作「秋」ですが、私はこの詩を読んだ時、ドイツ人の私にも、すぐに頭の中に情景が浮かんできました。

峰岸順子(以下、峰岸):自分が、農家だったので、稲とか田んぼのお仕事だったんですね。それで、秋には耕具機、機械で田んぼを耕したりするんですけれど、そういう秋の情景を書いたものです。ザンダー先生にもイメージしてもらえたということで、よかったです。

ザンダー:峰岸先生の詩は、ドイツの詩と似た印象がありますね。読んだ時の音の感じや、リズム感が似ているように思ましたが、詩にとってこれらの点はとても重要ですよね。このようなオリジナリティのある詩というのは、どうやって作られているのでしょうか?

峰岸:作品は、その時々の、まったくの衝動書きです。詩ができる時というのは、その時、瞬間の気分と言いますか、内から湧き上がってくるものがあるんですね。余すことなく表現するには、衝動書きが一番だと思うんです。

ザンダー:私は、創造という作業において、踊り、音楽、絵画が柱であると考えてきました。しかし日本に来て、峰岸先生のように優れた詩人の作品を読んだことで、そこに四つ目の柱として詩を加えなくてはいけないことを学びました。

峰岸:ありがとうございます。

ザンダー:峰岸先生の衝動書きという手法の話で、第一次世界大戦の頃に流行したダダイスムス(英語表記ではダダイズム)を思い出しました。これは、世界大戦の影響でスイスへと逃れた世界各国の詩人たちの芸術運動で、戦争に対する抵抗や、その結果としての虚無感を根底に持った創作を行っていました。そのため、今までの芸術の歴史や経験、考え方を否定するもので、その結果として意識的な行いをすべて否定して、無意識的で意味の無いものを作ろうとしたんです。ですから詩は、ただの言葉のリズムと発音しかない。

峰岸:やり場のない思いを表現しようとしたのでしょうかね。リズムや音だけでというと難しいのではないかと感じますが、その表現のためには必要なことだったのかもしれませんね。

ザンダー:本当に、峰岸先生のおっしゃる通りだと思います。衝動書きのお話で、内から湧き上がってくるものがあるから詩が書けると言われましたよね。私は詩ではなく絵ですが、風景を描く際は、葉っぱを1 枚1 枚とか書くんではないんですね。キャンバスの前に立って、描き上げるまで、誰とも絶対話しません。どうしてかっていうと、自分はその世界にいて、その世界から引き戻されたくないからです。自分の世界の中でその景色を見て、そして、色とかリズムだとか、そういうものが自分の中に流れてくるんですね。その流れを書いているんですね。

峰岸:そうですね、そして私はそれがいつ出てくるかわからないから衝動書きであって、浮かんだ瞬間にすぐ書き留めるんです。

ザンダー:ただ、その世界というのは、人それぞれなんですよね。1 人で、その世界に入っていく。詩も同じだと思うんですけども、その中に入っていく。そのとき、それぞれ、10 人の人がいれば、10 人違うふうに入っていくかもしれない。でも、それでいいんだと思うんですね。誰かが、これはこうだという必要は全くないわけで。全ての創造物というのは、似ているのかもしれません。最後に、日本とドイツ双方で活躍されている峰岸先生から見て、両国の交流がこれからさらに深まる上で、どんなことが必要と思われますか?

峰岸:人には、それぞれに、色々な思いや願いがあると思うんです。生活にしても、平和にしても。そういう思いを表した芸術、例えば詩や絵などを、お互いに鑑賞し合えることが大切なのではないでしょうか。相手の国の芸術作品について、作者の制作意図や心情を、お互いに理解することをきっかけに、さらに相手の国への理解や気持ちが深まると思います。

ザンダー:まったくそのとおりですね。私は今回初めて日本にやってきて、日本の芸術家からお話を伺う機会を得ましたが、当初は戸惑いや不安もありました。しかし峰岸先生が言われたように、芸術家同士だと、お互いの思いとか、心情などが、お互いの創作活動や作品を通して、伝わってくるんです。おかげで今日も、峰岸先生との貴重な時間を楽しむことができたというわけです。今日は本当にありがとうございました。もしまた次の機会があれば、より峰岸先生と先生の詩について、理解が深まることでしょう。

(2019年特別対談 峰岸順子×クラウス=メンツ・ザンダー)

The representatives of poetry and paintings explore the source of creation beyond genres

Klaus Menz-Sander (hereinafter referred to as “Sander”): Seeing as how you are a poet and I am a painter, I would like to have a conversation with you today about your thoughts on poetry as well as the differences that we have in our artistic expression. First of all, I’d like to mention that even as a German, I was able to immediately picture the scene as I was reading “Fall,” which was the poem you exhibited this time.

Yoriko Minegishi (hereinafter referred to as “Minegishi”): I was a farmer, so I used to work with rice and paddy fields. During the fall, I would also plow through the paddy fields with my farming tools and machines. So I wrote this poem while having this particular scene in mind. I’m glad that you were able to picture this scene too.

Sander: The impression that your poem gives off is similar to that of German poetry. I thought that it was similar in terms of the sound and the rhythm I felt as I was reading it. These two aspects are very important in poetry. So how do you write such an original poem like this?

Minegishi: My works are pieces of writing that I write out of complete impulse from time to time. At times when I’m able to write a poem, there’s a feeling that bubbles up from inside of me. So I think impulse writing is the best way of expressing myself without leaving anything behind.

Sander: I’ve always considered dance, music, and painting to be the pillars of creation. However, when I came to Japan and read the works of excellent poets like yourself, I learned that poetry had to be added as the fourth pillar of creation.

Minegishi: Thank you.

Sander: As you were talking about your technique of impulse writing, I was reminded of Dadaism, which was a popular artistic movement during World War I. Dadaism was followed by poets from countries all over the world who fled to Switzerland as a result of the war. The artworks that were formed under this movement were created based on the artists’ resistance to the war as well as the sense of void they had felt due to the war. So what these artists did at the time was to create unconscious and meaningless pieces of art that resisted all conscious efforts and defied all prior history, experiences and philosophies in art. Therefore, poetry was nothing more than just the rhythm and pronunciation of words back then.

Minegishi: I guess these artists were just trying to express the overwhelming emotions they were feeling. I also feel as though writing a poem based on rhythm and sound alone would be difficult, but this may have been something that was needed in order to express those sort of emotions.

Sander: I think you’re completely right about that. When you were talking about impulse writing, you mentioned that you were able to write poems because of a feeling that bubbles up inside of you. For me, when I paint sceneries, I don’t really paint every single leaf I see. I simply just stand in front of my canvas and paint without speaking a word to anyone until I’m done. I do this because when I’m painting, I feel as though I’m in another world that I do not wish to be pulled back from. Also, when I’m looking at the scenery within my own world, I can sense the colors and rhythms flowing through me as well. So I paint while being guided by these sensations.

Minegishi: Well for me, I write on impulse since I’m not really sure when the feeling will come up. And whenever it does come up, I make sure to write something down immediately.

Sander: But the “world” I mentioned earlier is something that varies depending on the individual. So it’s a world that each person goes into alone. I think it’s the same with poetry, since there must be a different world that poets go into as well. So if there are ten people writing a poem, all ten of these people may have different ways of entering into this world. But I think it’s fine this way since there’s no need for anyone to dictate how things should be. If this wasn’t the case, then all creations may end up being similar to one another. Lastly, as someone who’s active in both Japan and Germany, what do you think is needed in further deepening the exchange between the two countries?

Minegishi: I think each person has their own feelings and desires concerning things such as life and peace. So it’s important for us to be able to mutually appreciate the poetry, paintings and other forms of art we create that express such feelings. I think that gaining a mutual understanding about the artistic intentions and feelings behind each other’s artworks will also allow the two countries to foster a deeper understanding and sentiments towards one another.

Sander: That’s exactly right. Since this is my first time coming to Japan and being given such an opportunity to interview Japanese artists, I felt confused and uneasy at first. But just like you said, when artists are together, we’re able to express our feelings and sentiments to one another through our creative activities and works. Thanks to this, I was able to enjoy the precious time that I had with you today. So thank you very much for today. If I were to be given the opportunity to meet you again next time, I would surely gain a better understanding of you and your poems.

(2019 Special Talk: Junko Minegishi and Klaus Menz-Sander)

家族との日々に愛を込めて綴る慈愛の詩人

峰岸順子(以下 峰岸):初めまして、峰岸順子です。今日はよろしくお願いします。

アニータ:こちらこそよろしくお願いします。アニータと申します。さっそくですが、今回の峰岸先生の詩についてお聞かせください。

峰岸:私の詩作は、日常の中でふっと感じたことを書き留めていく、その時々の衝動書きなので、いつ詩ができるか、私自身でもわからないのですが、詩作は自分自身の自然な気持ちの成り行きにゆだねています。

アニータ:芸術というのは、計画してできるものではありませんよね。純粋であればあるほど、突然生まれるものではないでしょうか。

峰岸:私の場合、詩というのは、私の心の中に流れる音楽のように捉えています。作ろうと思わず、意識せずにいる方が大切なのかもしれません。今回の詩は、赤ちゃんのことを詠った詩ですが、まだ見ぬお腹の中で成長している赤ちゃんへ、やがて生まれてくる赤ちゃんへの語りかけを書いた詩です。

アニータ:峰岸先生のお話を聞いていると、詩を作ることを本当に楽しんでいらっしゃるとわかります。そもそも詩は、短い文章の中で自分の心をしっかりと伝えなければいけません。普通の方々が思っているよりもはるかに難しい芸術です。心に感じたことを、他の人にもわかりやすく伝え、なおかつ同様の気持ちを体験させるというのは、本当にすごいことだと思いますよ。

峰岸:そう言っていただけるのはありがたいことです。ただ私自身は、出てくる言葉を書きとめ続ける中で、作品ができ上がっていくだけなのですよ。

アニータ:しかし峰岸先生の詩は、日欧の芸術交流で大きな役割を果たされています。少なくともヴェネチアでは、先生の詩を通して多くの人間が日本の現在を知ることができました。先生ご自身では、自分の詩を通じて今後どんなことができれば良いと思われますか?

峰岸:何か特別な思いを抱いたことはないですね。ただ、私とは年齢の離れた妹へのメッセージのつもりで、自分の心の記録をまとめたものですが、書き溜めたものを他の人たちにも見てもらえればという思いが芽生えまして。それで、これまでの積み重ねをまとめて本にしたんです。ところがその本をきっかけにして、いろいろなところからお声がけをいただくようになって、展覧会などを通じて国内外の様々な場所で私の詩を見てもらうことができるようになりました。本を出した時は、こんなことになるとは思ってもみませんでしたね。そういう意味では、自分は恵まれていたんだなと思います。

アニータ:やはり自分の思いを他の人に感じてもらえるというのは、特別なことですよね。その事実を通して、自分自身もさらに学び成長することができますね。

峰岸:そうですね、ですからこれまでの私自身の活動というのは、本を出したことだけなんです。展覧会などに出していただくことは、自分主導でできることではありませんので。これからも何か自分が特別に活動をしていくことはないと思います。

アニータ:しかし言葉が話せるかどうかと関係なく、感動的な物事を言葉に表現できるのは素晴らしいことです。ほとんどの人は、自分の気持ちを余すことなく言葉にすることはできません。ところが峰岸先生の詩を読むことで、先生の感動を共有し、同時に自分自身の感動を知ることができます。私も今回の先生の作品を読むことで、我が子が生まれた時の感動を思い出しました。自分で表現できなかった言葉が、先生の詩によって見事に表されているわけです。

峰岸:ありがとうございます。

アニータ:これからの創作活動についてはいかがですか? どんな詩を作ってみたいですか?

峰岸:衝動書きで生まれるのが私の詩なので、意図的にこういうものを作りたいと思っても、なかなか難しいですね。ただ、いつでも詩に詠えるような感動ができる、そういったみずみずしい心を持ち続けていたいです。

アニータ:最後に、国際化が進む現代の中で、芸術はどのように関わっていくと思われますか?

峰岸:表現することは、お互いを知るための第一歩だと思うんですよ。たとえ人種や文化が違っても、何か感じるものはあるはずですから。それを相互に伝え合うことで、互いを理解し合えるようになり、平和へとつながっていくのではないでしょうか。そういった点でそれぞれの思いや願いを表現できる芸術は、平和への大きな役割を担っていると思います。

アニータ:私もまったく同じ考えの元に活動しています。ぜひ言葉を超えた相互理解のため、頑張りましょう。今日はありがとうございました。

(2018年特別対談 峰岸順子×アニータ・チェルペッロニ)

A compassionate poet who writes lovingly about

her days with her family.

Yoriko Minegishi: Hello, my name is Yoriko Minegishi. I’m happy to be here today.

Anita: I’m Anita. Thank you for making the time to talk with me today. I’d like to ask you about your poems, if I could.

Minegishi: The way I create poems is I write down the things that occur to me throughout the day. And since I only occasionally get such impulses, I never know when a new poem will get written. I let my muses decide.

Anita: I understand — art isn’t something that gets made on a schedule. It comes out, suddenly, the closer we listen to our hearts.

Minegishi: Poetry, to me, is like music flowing through my heart. Just being present — without intending to make it or be conscious of it — is the important thing. This poem is an ode to babies. It speaks to babies nobody has yet seen, growing bigger in the womb, to babies whose birth is in the offing.

Anita: Talking with you, I can really feel how much you enjoy making poems. Poems are supposed to be things that convey, in short sentences, what’s in the heart. It is a much more difficult pursuit than most people think. Communicating what’s in the heart to someone else in a readily-understandable way and getting them to feel the same emotions — that’s really something special.

Minegishi: It’s very gratifying to hear you say that. But in my case, I am simply continuing to write down the words that come. The poems simply form by themselves.

Anita: Your poems play a big role in artistic exchange between Japan and Europe. In Venice, at least, many people have learned much about how Japan is today through your poems. Going forward, is there anything that you hope to be able to accomplish through your poems?

Minegishi: I’ve never had any such special ambition. But my poems were originally intended to be messages — records of what was in my heart — for my much younger sister. Nowadays I’m happy for others to read them, as well. That is what made me put all of my poems together into a book. And since I released the book, I have been hearing from people all over, and I have found readers in so many places in Japan and elsewhere through art exhibitions and other things. I never imagined that this would happen when I released the book. I consider myself blessed in that sense.

Anita: Having someone else understand your feelings is truly something special, isn’t it? That fact is what allows us to achieve further learning and growth.

Minegishi: Exactly. And because I have no control over whether my pieces appear at exhibitions and things, the only thing I’ve yet done myself as a poet has been to release this book. In the years ahead, I don’t think I will be doing anything else like this.

Anita: But it’s wonderful how you can express inspirational things in words, regardless of whether or not you can speak the language. Very few people can fully express how they feel in words. Reading your poetry, I can feel he things that move you while at the same time feeling moved, myself. When I read this poem, I was reminded of the excitement I felt when my own child was born. The words that didn’t come to me at the time are beautifully articulated in your poems.

Minegishi: Thank you.

Anita: How do you see your career as a poet going forward? What kinds of poetry do you want to write?

Minegishi: My poems arise from impulsively putting words to paper; willfully attempting to write one doesn’t really work for me. Still, I do hope to always keep that youthful frame of mind that allows me to feel things that I could make into poetry at any time.

Anita: Lastly, what role do you think art will have in our increasingly globalized world of today?

Minegishi: Artistic expression is the first step to understanding each other. Though we may differ in race or culture, we all feel things. Expressing these feelings to each other lets us understand one another, which I believe leads to peace. It is through art that we can each express our thoughts and hopes, which makes it an important part of achieving peace.

Anita: That exact philosophy is what guides me as an artist, as well. Let’s keep doing what we do — to better understand each other regardless of linguistic barriers. Thank you for talking with me today.

(2018 Special Talk: Junko Minegishi and Anita Cerpelloni)

Art History /アートヒストリー

序文

詩人・歌人として活躍する峰岸順子。1976年に「わが愛の詩」を刊行以降、その活動歴は40年を超えるが、一貫して“愛”の表現にこだわり続けている。文学に憧れた子ども時代、辛い別れを乗り越えた青春時代、そして本格的に文芸と向き合い始めた社会人時代…

ここでは彼女の山あり谷ありの半生の中で育まれてきた“愛の文芸”の軌跡を紹介したい。

幼少期

峰岸順子は昭和14年3月1日、福島県の須賀川町(現在の須賀川市)に生まれました。兄妹6人に祖父母も同居する大所帯で、非常に賑やかな家庭だったと言います。

須賀川は、旧石器時代の乙字ヶ滝遺跡や、奈良・平安時代の上人壇廃寺址が発掘されるなど、歴史深い土地として知られます。鎌倉時代には有力御家人として名を馳せた二階堂氏の城下町として栄えましたが、戦国時代には伊達政宗の侵攻を受けて陥落し、江戸時代以降は白河藩の宿場町として発展しました。

現在の須賀川市は東北第二の規模を誇る郡山都市圏の一角を形成する他、市内には福島空港を擁するなど、東北の玄関口としても知られます。

しかし県東部を東北第二の長さを誇る阿武隈川が縦断するなど水資源が豊富であることから、農業を生業とする人々が非常に多い地域でもあります。峰岸の実家も代々続く農家で、父も母も祖父母も朝から晩まで忙しく働いていました。そんな日常にあって峰岸の遊び相手になったのは、須賀川の豊かな自然でした。「学校帰りに道路を歩かずに川の淵を歩いたり、山越えをして帰ったり、山の中を歩いたりとか。みちくさが好きでしたね。遠回りばっかりしていました。」

こうした自然との戯れで目にした風景は、やがて文芸創作を行う上で、美的感覚を養う重要な経験となりました。

一方、詩との出会いは、小学校四年生の時に担任の先生から出された詩作の課題でした。実はそれ以前にも自分の気持ちを言葉に書き留めていたのですが、あくまでも取り留めない思いつきに過ぎなかったと言います。しかしこの詩作との出会いによって、それまでの書き留めに「詩作」という素晴らしい名前がもたらされたのです。

学生時代

地元で中学・高校と進学した峰岸は、詩との出会いを経て、文学への関心を高めていきます。学校の図書館に足を運ぶことも増え、様々な小説や詩集を読み漁って言語感覚や文章表現を養い、自分自身の詩作を成長させていきました。

しかし詩の作り方自体は、意外にも当時と今とで変わりはないと言います。

峰岸の詩作方法は“衝動書き”。

思ったこと、感じたことをそのまま言葉にしていくことで、その瞬間の自分の感情を表現します。この下地になっているのは、もちろん幼少期から続けてきた書き留めです。より良く見せるのではなく、あくまでも自分自身のやりたいことは貫くという表現者としての信念が、すでに備わっていたのでしょう。

その信念を象徴するのが、20歳から始めた短歌の話です。詩作とほぼ同時期から短歌にも興味があった峰岸ですが、あえて自分で詠むことは避けていたと言います。これは和歌独自のリズムや文字数の制限・さらに季語や本歌取などの独自の美観が、若い自分にはかえって足かせになってしまうのではないかと直感的に理解したゆえの判断でした。

そんな峰岸を突然の悲劇が襲ったのは、彼女が高校に進学して間もない頃のことでした。母が41歳の若さで突然他界してしまったのです。仕事柄、常に家にいる人ではありませんでしたが、母親に先立たれた喪失感は今も胸に残っています。峰岸は文芸作家デビュー後も母親を題にした歌が少なくありません。

ふる里の墓に眠れる母よりも 年上となりて母なお愛し

峰岸には、今も忘れられない母親との思い出があります。

「うちの母は日が沈むまで働いているんですね。そこで母を迎えに行った道中でのことですが、空に光る北極星と北斗七星の話を教えてもらいました。母に教えてもらったというのが自分の中ではとても大切な思い出で、それを思い出すと今なお幸せになれます。」

そんな彼女を支えたのが、たくさんの家族と詩作でした。

中でも高校の同級生くるまだ菊枝さんとの親交は、峰岸の詩にも大きな刺激を受けたと言います。大きな悲しみを乗り越えて、やがて峰岸は豊かな創作を広い世界へと解放していくのです。

文芸作家として

峰岸が本格的に文芸作家としてデビューしたのは、思いもよらないきっかけからでした。嫁いだ際に嫁入り道具として持ち出した箱を開けてみた時、中から学生時代の詩の書き留めがたくさん出てきたのです。驚くと共に懐かしい気持ちを思い起こした峰岸は、書き留めを元にして九つ年下の妹にメッセージを綴ろうと思い立ちます。

それをきっかけにして出版されたのが、自費出版の処女作「わが愛の詩」でした。もちろん刊行当時(1976年)は自費出版なんて極めて珍しいことでしたから、どうして良いのかわからない、まさに試行錯誤の編集・出版でした。自由になるお金もないので、編集も校正も、できることは全て自分でやりました。

こうして悪戦苦闘の日々はひとまず妹に本を届けて一旦終了となりましたが、詩人としての峰岸順子の始まりは、むしろここからだったと言います。書籍は近隣の図書館や高校など公共施設に配本され、幅広い年代の人々が峰岸の詩を読み、彼女の人生とその折々の言葉に大きな感動をもたらしました。

さらに20年後、「わが愛の詩」を通して他の出版社から再び本を出版しないかとのオファーが届きます。ちょうどその頃、峰岸自身も自分の人生を紡いできた作品を残したいという思いが芽生えていたこともあり、それはまさに巡り合わせのように思われました。

以降、峰岸の文芸は、大きな広がりを見せています。2023年現在、世界5カ国語以上に翻訳され、日本はもちろん、ドイツやフランス、イタリア、カナダなど各国で作品が読まれ、高い評価を受けてきました。とくに近年は世界情勢の乱れが顕著であり、平和的な思考や人と人とのつながりを求めていたことも、大きかったと考えられます。彼女の愛の言葉は、元々は家族への小さな思いやりの産物でした。しかしその広がりは、これからも多くの人々に読み継がれていくことでしょう。

Introduction

Yoriko Minegishi has flourished as a poet. Since the publication of My Love Poems in 1976, Minegishi has been active as a poet for over 40 years, consistently dedicating her work on expressing “love” during this time. She had gone through a childhood of admiring literature, adolescent years overcoming a painful loss, and officially taking on literary arts as a career.

Here, we would like to introduce the trajectory of Minegishi’s “literature of love” developed over the course of her life journey full of ups and downs.

Early Childhood

Yoriko Minegishi was born on March 1, 1939 in Sukagawa Town (now Sukagawa City) in Fukushima Prefecture. She came from a very lively, large family with six siblings, and she lived together with her grandparents.

Sukagawa is known as a land with a rich history.It is home to the ruins of Otsujigataki Falls from the Paleolithic period and the site of an abandoned Buddhist altar from the Nara and Heian periods. During the Kamakura period, it prospered as the castle town of the Nikaido clan, who were famous as influential vassals. However, during the Sengoku period, the town fell after invasion by Masamune Date, and since the Edo period, it developed as a post town for the Shirakawa clan. Today, Sukagawa City forms part of the Koriyama metropolitan area, which is the second largest urban area in the Tohoku region. It is also known as the gateway to the Tohoku region, with Fukushima Airport located in the city. Despite its urban development, since the area is rich in water resources with the Abukuma River, the second longest river in Tohoku, traversing the eastern part of the prefecture, it is also home to many farmers. Minegishi’s family has been farmers for many generations, with her parents and grandparents also busy working day and night.

Under these circumstances, the rich nature of the Sukagawa River became Minegishi’s playmate. “On the way home from school, instead of walking on the road, we walked along the edge of the river, went over the hills, or walked in the mountains. I liked meandering. I was always taking detours. ”

The scenery she witnessed in her time spent with nature helped to foster her artistic sense used to create literary works.

At the same time, her encounter with poetry began with a homework assignment to compose a poem, which was given from her fourth grade homeroom teacher. Prior to this, she had written down her feelings, but these were nothing more than her simple musings. This encounter with poem writing, however, brought about the wonder of poetry composition to her previous writings.

School Years

Minegishi, who attended a local junior high and high school, became interested in literature following her encounter with poetry. She began to go to the school library more often, fostering a greater sense of language and compositional expression by reading various novels and poetry compilations. This also advanced her poetry composition skills.

Today, however, her approach to composing poetry surprisingly remains unchanged from her student days.

Minegishi’s approach to poetry involves “impulse writing.”

By using words to describe exactly what she is thinking or feeling, she is capable of instantly expressing her emotions at the moment. The foundation of this skill, of course, lies in the countless writings she’s been practicing as a child.

She must have already had the conviction as an artist not to make things look better, but to stick to what she wanted to do.

A symbol of this conviction is the story behind her tanka, or short Japanese poems, which she began at the age of 20. Minegishi had an interest in tanka poetry during the same time as when she learned poetry composition, but she chose to avoid reciting her work. This was a decision made because she intuitively understood that the unique rhythm and character limitation of waka poetry, as well as the unique aesthetics of kigo (seasonal words) and honkatori (adaptation of a famous poem), would be a hindrance to her young self.

It was then that tragedy struck Minegishi soon after enrolling in high school. Her mother suddenly passed away at the young age of 41. She was not always at home due to work, but Minegishi still remembers the sense of loss from her mother’s departure. Even after making her debut as a literary writer, many of Minegishi’s poems were about her late mother.

My grandmother used her arms as a pillow to sleep next to my late mother’s body after she passed in her forties

I’m now older than my mother who sleeps in the grave of our hometown, and I still love her

To date, Minegishi still has memories of her mother she will not forget.

“My mother worked until the sun went down. One day I walked to pick her up and on the way home she told me about the North Star and the Big Dipper shining in the sky above. This remains a very important memory of my mother. Recalling these memories brings a smile to my face. ”

Poetry composition and her large family helped to get her through this hard time.

Among her connections, her friendship with high school classmate Sakue Kurumada greatly stimulated Minegishi’s poetry. Overcoming this immense tragedy, Minegishi would eventually release her vibrantly creative works to a broader audience.

Career as a Literary Writer

Minegishi made hew official debut as a literary writer under somewhat unexpected circumstances. After getting married and moving in with her husband’s family, she found a number of her poems from her student days inside a box. Minegishi was surprised, and also felt a wave of nostalgia come over her. She decided to write a message to her sister nine years younger to her based on the writings she found.

This led her to self publish her maiden work called My Love Poems. Of course, it was rare for an author to self publish back in 1976. Unsure of the process, editing and publishing was filled with trial and error. With little money to spare, from editing to proofreading, she did everything she can on her own.

While her days of struggle ended for the time being with the delivery of the book to her sister, this marked the beginning of Minegishi’s journey as a poet. The book was distributed to nearby libraries, high schools, and other public facilities. People of all ages read Minegishi’s poems. The story of her life and her words used at every stage greatly moved their hearts.

Two decades later, through My Love Poems, she received offers from other publishers to publish the book again. Around that time, Minegishi had a growing desire to share the works that had spun her life, it seemed like a perfect opportunity that felt like fate.

Since then, Minegishi has greatly expanded on her work in literary art. As of 2023, her work has been translated into more than five languages and they have been highly praised around the world, with readership in Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Canada, among other countries. This is likely because people are seeking peaceful thoughts and connections between one and another, following the major turmoil facing the world in recent years.

Minegishi’s language of love was derived originally from her simple compassion for her family. We hope that more and more people will be able to read and pass down her work to others.

Solo Exhibition /個展

特設個展ブース in アートビエンナーレ2021

会期:2021年6月4日~6日

会場:The ART HOUSE(シンガポール)

企画・運営:クリエイト・アイエムエス株式会社

Special Exhibition Booth in Art Biennale 2021

Dates: June 4-6, 2021

Venue: The ART HOUSE, Singapore

Planning and operation: CREATE IMS Co.

特設個展ブースin 日欧宮殿芸術祭2021

会期:2021年6月4日~6日

会場:シャルロッテンブルク宮殿(ドイツ・ベルリン)

主催:一般社団法人 日欧宮殿芸術協会

運営:クリエイト・アイエムエス株式会社

Special Exhibition Booth in JEPAA Festival 2021

Dates: June 4-6, 2021

Venue: Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin, Germany

Organizer: Japan-Europe Palace Art Association

Operated by: Create IMS Co.

Profile /経歴

峰岸順子 Yoriko Minegishi

1939年 福島県出身

作品出展国遍歴(JEPAA関連事業):ドイツ、フランス、マルタ、カナダ他

Born: 1939 Fukushima, Japan

Exhibition of Works(JEPAA): Germany, France, Malta, Canada…

-01-430x513.jpg)

-01-445x987.jpg)

-445x479.jpg)